False Friends: the Adoption of Foreign Terminology in English<>Spanish Medical Translation and Interpretation

Written by Paula Penovi

ATA-Certified Translator and Certified Medical Interpreter (CMI-Spanish)

As a linguist working at a hospital, it is not uncommon to notice languages merge and blend into each other, adopting foreign terms and structures and converging into a complex hybrid language. As we all know, communication is critical to ensure successful healthcare. Lexical borrowings, calques and literal translations that may sound natural to the untrained ear could end up leading away from the meaning that was originally conveyed, while contributing to the impoverishment and erosion of the target language.

That is why today I am going to share some insight into four of the most common false friends that I have encountered in the medical setting, their polysemy and some lexical equivalents and alternatives. False friends (also known as false cognates) are words that look very similar and appear to be translation equivalents, but which actually have different meanings in different languages.

Since we are focusing on some of the most frequent terms that an interpreter or translator will encounter on an everyday basis, the first place must go to ‘condition,’ when it is translated as condición. Quoting Dr. Fernando Navarro, whenever this word is used to refer to a defective state of health, it can be translated as enfermedad (skin condition = enfermedad cutánea), proceso (pathologic conditions = procesos patológicos), dolencia, afección (surgical condition = afección quirúrgica), trastorno or cuadro clínico. Whenever it refers to the particular state that something or someone is in, it can be translated as estado (critical condition = en estado crítico) or situación (stable condition = en situación estable), and sometimes the interpreter or translator has to use their best judgement and choose a translation based on the context, as in the case of ‘clinical condition’ (cuadro clínico, estado clínico or situación clínica).

Another word that I hear mistranslated a lot is ‘severe.’ It is not uncommon to find severo used as an equivalent, term which in Spanish means ‘strict, tough, harsh in treatment or punishment’ and is only used to describe the character of a person. In English, it can have many different meanings: grave (severe condition = en estado grave), intenso (severe pain = dolor intenso, agudo), fuerte (a severe blow to the head = un fuerte golpe en la cabeza) or extenso (severe psoriasis = soriasis extensa). It goes without saying that sometimes only the context can define the most accurate translation for this term: for example, ‘he had a severe loss of blood’ could be translated as ‘perdió mucha sangre’.

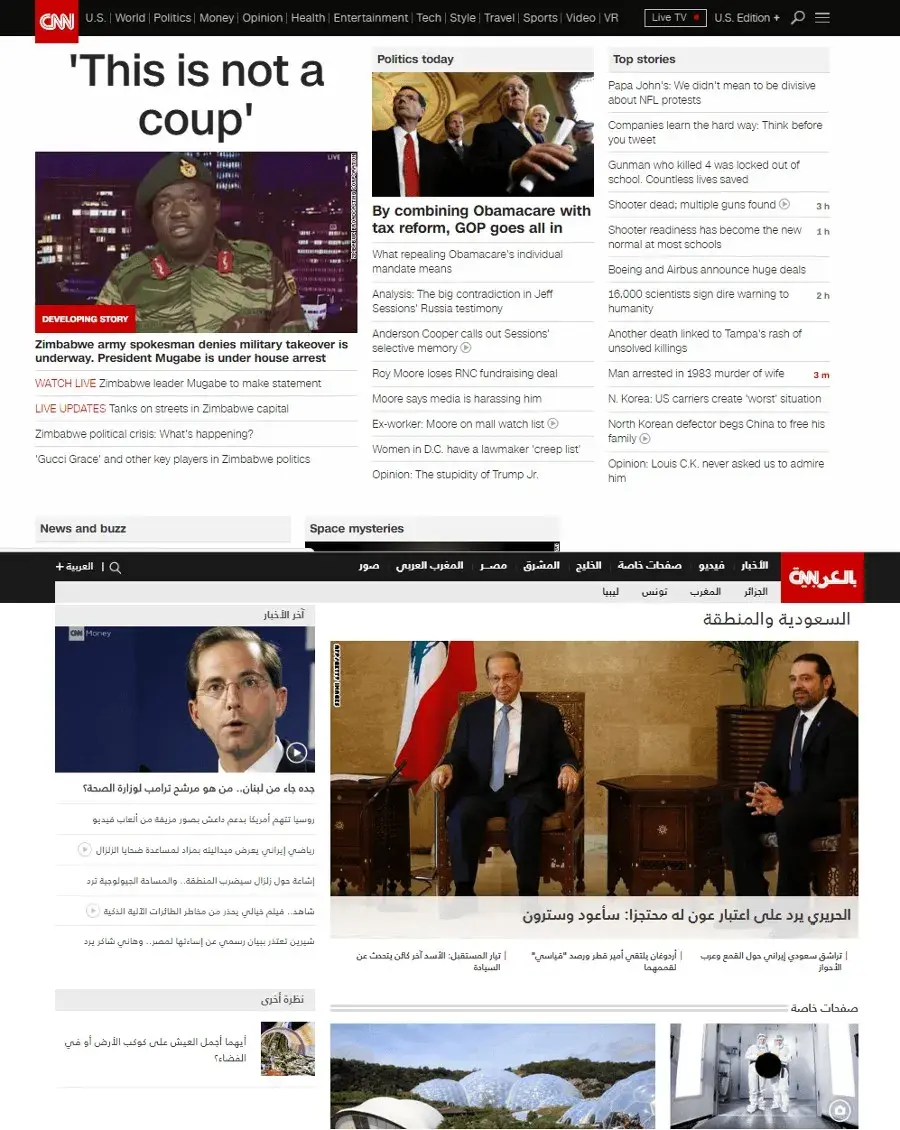

In 1980, a patient was taken to a hospital in a coma and his family used the word intoxicado to refer to his condition, since they thought his symptoms were caused by something he had eaten. This word was mistranslated as ‘intoxicated’ during the encounter, and in consequence the doctor immediately made a misdiagnosis of drug overdose, causing the patient to become quadriplegic at age 18. There is a lot to say about this false friend, but we can start with the fact that, in Spanish, intoxicado refers to food poisoning (intoxicación alimentaria, toxinfección alimentaria), while in English ‘intoxicated’ is related to the effect of alcohol or drugs. During regular medical encounters, the word ‘poisoning’ will most likely refer to intoxicación instead of envenenamiento (malicious poisoning). For instance, accidental poisoning would usually be translated as intoxicación involuntaria and acetaminophen poisoning as intoxicación por paracetamol. While intoxicación might seem to be the best equivalent in this setting, when using a more technical language, translators and interpreters will have to resort to a word ending in ‘–ismo’ in Spanish: cheese poisoning (tirotoxismo), fish poisoning (ictiotoxismo), lead poisoning (saturnismo) and blood poisoning (toxemia or septicemia), among others.

Last but not least, I would like to discuss one of my personal favorites, a Gallicism widely used both in English and Spanish: the term ‘control.’ Even though it seems easy to avoid translating this term literally in cases such as ‘birth control’ (regulación de la natalidad, reducción de la natalidad, anticoncepción) or ‘centers for disease control’ (centros de epidemiología), we tend to be unoriginal when faced with verbal phrases and collocations that come up all the time during medical encounters. For instance, we tend to stay in our comfort zone and resort to this word when translating phrases such as ‘controlar una hemorragia’ (detener, restañar), ‘controlar la tensión arterial’ (medir, vigilar, estabilizar, normalizar), ‘control de la temperatura corporal’ (regulación), ‘controlar los efectos de una sobredosis’ (neutralizar), ‘controlar una anemia’ (corregir); the list could go on forever. In this regard, Dr. Fernando Navarro presents an exhaustive list of alternative translations for this term in his dictionary, and I believe it would be interesting to mention a few to shed light on the variety of linguistic choices the Spanish language has to offer: getting/to get a situation under control (dominar una situación), control of an epidemic (contención de una epidemia), disease control (lucha contra las enfermedades), control visit (consulta de revisión), food control laboratory (laboratorio de bromatología), self-control (autodominio), temperature control (termorregulación), case-control study (estudio de casos y testigos).

After exploring all these equivalents, one wonders why it is so easy to forget the richness and beauty of our native language and to embrace this constant influx of foreign terminology. Only professional translators and interpreters can at all times recognize this dilution of language and make the most accurate choice in the right context. Continuing education plays a key role in helping us celebrate our own lexical items and structures, value them and avoid these frequent and deep-rooted mistranslations. This is only one of the reasons why there needs to be an emphasis on certified translators and interpreters in the medical field. If you are seeking translation or interpreting services, make sure you choose your language professionals wisely. In the long run, the costs of professional services are likely to be far less than the costs of the clinical error claims that may arise from these incidents in a healthcare setting.

References:

Diccionario de dudas y dificultades de traducción del inglés médico, by Fernando A. Navarro

In The Hospital, A Bad Translation Can Destroy A Life, by Kristan Foden-Vencil

Language, Culture, And Medical Tragedy: The Case Of Willie Ramirez, by Gail Price-Wise

Medical English and Spanish cognates: identification and classification, by Lourdes Divasson and Isabel León

Severe: A False Friend, by G. Blasco-Morente, C. Garrido-Colmenero, J. Tercedor-Sánchez and M. Tercedor-Sánchez

Cambridge Dictionary

Online dictionary by Merriam-Webster

The Royal Spanish Academy’s Dictionary